- Linear Regression

- Cost Function

- Gradient Descent

I am learning about Machine Learning via the course offered by Coursera named: Machine Learning by Stanford University. This post covers Week 1 materials.

What I learnt:

Model Representation in Linear Regression

E.g. 1: Housing price data (example used in earlier post)

Supervised learning - regression problem

What do we start with?

- Training set (this is your data set)

-

Training set of housing prices (Portland, OR):

-

Notation (used throughout the course)

- m = number of training examples

- x = “input” variables / input features: (living area in this example)

- y = “output” variables/ “target” variables (price)

- (x,y) - A pair of x, y is called single training example

- (x i, y i) - specific example (ith row of training set)

- We will also use X to denote the space of input values, and Y to denote the space of output values. In this example, X = Y = ℝ

With our training set defined - how do we used it?

Take training set

Pass into a learning algorithm

Algorithm outputs a function (denoted h ) (h = hypothesis)

This function takes an input X (e.g. size of new house)

Tries to output the estimated value of Y (e.g. estimated housing price)

How do we represent hypothesis h?

- hθ(x) = θ0 + θ1x

- h(x) (shorthand)

- What does this mean?

- This function shows that Y is a linear function of x

- θi are parameters

- θ0 is zero condition

- θ1 is gradient

- This kind of function is a linear regression with one variable

- Also called univariate linear regression

- What does this mean?

When the target variable that we’re trying to predict is continuous, such as in our housing example, we call the learning problem a regression problem.

When y can take on only a small number of discrete values (such as if, given the living area, we wanted to predict if a dwelling is a house or an apartment, say), we call it a classification problem.

Summary:

- A hypothesis takes in some variable

- Uses parameters determined by a learning system

- Outputs a prediction based on that input

Cost Function in Linear Regression

We can measure the accuracy of our hypothesis function by using a cost function.

This takes an average difference (actually a fancier version of an average) of all the results of the hypothesis with inputs from x’s and the actual output y’s.

A cost function helps us find the best fit straight line to our data.

Choosing values for θi (parameters)

- Different values give different functions

- If θ0 is 1.5 and θ1 is 0 then we get straight line parallel with X along 1.5 @ y

- If θ1 is > 0 then we get a positive slope

Based on our training set we want to generate parameters which make the straight line.

- Choose θ0, θ1 so hθ(x) is close to y for our training examples

- Basically, use xs in training set with hθ(x) to give output which is as close to actual y value as possible

- Think of hθ(x) as a “y imitator” - it tries to convert the x into y, and considering we already have y we can evaluate how well hθ(x) does this

- To formalize this,

- We want to want to solve a minimization problem in linear regression

- Minimize (hθ(x) - y)2

- i.e. minimize the difference between h(x) and y

(e.g. to minimize the square difference between the output of the hypothesis and the actual price of a house)

- i.e. minimize the difference between h(x) and y

- m here was the size of my training set

- Sum this over the training set

Minimize squared difference between predicted house price and actual house price

- 1/2m

- 1/m - means we determine the average

- 1/2m the 2 makes the math a bit easier, and doesn’t change the constants we determine at all (i.e. half the smallest value is still the smallest value!)

- Minimizing θ0/θ1 means we get the values of θ0 and θ1 which find on average the minimal deviation of x from y when we use those parameters in our hypothesis function

- More cleanly, this is a cost function J(θ0,θ1)

Cost function J(θ0,θ1) formula:

We want to minimize this cost function

- Our cost function is (because of the summation term) inherently looking at ALL the data in the training set at any time

Summary:

- Hypothesis - is like a prediction machine, enter a x value, get a putative y value

- Cost - is a way to, using your training data, determine values for your θ values which make the hypothesis as accurate as possible

- This cost function J(θ0,θ1) is also called the squared error cost function

- This cost function is reasonable choice for most regression functions

- Probably most commonly used function

Cost Function - Intuition I

Our objective is to get the best fit straight line

- such that the average squared vertical distances of the scattered points from the line will be the least

- Ideally, the line should pass through all the points of our training data set. In such a case, the value of J(θ0, θ1) will be 0.

Simplified hypothesis:

hθ(x)=θ1x+θ0

Assume θ0 = 0

- hθ(x)=θ1x

So hypothesis pass through 0,0

- Two key functins we want to understand:

- hθ(x) Hypothesis is a function of x - function of what the size of the house is

- J(θ1) Is a function of the parameter of θ1

- Examples:

Plot θ1 vs J(θ1) Data- θ1 = 1

J(θ1) = 0

- θ1 = 0.5

J(θ1) = ~0.58

- θ1 = 0

J(θ1) = ~2.3

- θ1 = 1

- If we compute a range of values plot

- J(θ1) vs θ1 we get a polynomial (looks like a quadratic)

- The optimization objective for the learning algorithm is find the value of θ1 which minimizes J(θ1)

- So, here θ1 = 1 is the best value for θ1

Cost Function - Intuition II

Using same cost function, hypothesis and goal as previously

Using our original complex hyothesis with two variables,

So cost function is J(θ0, θ1)

Example: if θ0 = 50 and θ1 = 0.06,

Previously we plotted our cost function by plotting θ1 vs J(θ1).

Now we have two parameters. Plot becomes a bit more complicated:

- Generates a 3D surface plot where axis are

- X = θ1

- Z = θ0

- Y = J(θ0,θ1)

Instead of a surface plot, we can use a contour figures/plots:

Contour plot: a graph that contains many contour lines.

Contour line: contour line of a two variable function has a constant value at all points of the same line.

- Set of ellipses in different colors

- Each colour is the same value of J(θ0, θ1), but obviously plot to different locations because θ1 and θ0 will vary

- Imagine a bowl shape function coming out of the screen so the middle is the concentric circles

Taking any color and going along the ‘circle’, one would expect to get the same value of the cost function.

- For example, the three green points found on the green line above have the same value for J(θ0,θ1).

The circled x displays the value of the cost function for the graph on the left when θ0 = 800, θ1 = -0.15.

Taking another h(x) and plotting its contour plot, when θ0 = 360, θ1 = 1.0, the value of J(θ0,θ1) in the contour plot gets closer to the center thus reducing the cost function error.

Now, giving our hypothesis function a slightly positive slope results in a better fit of the data. The graph minimizes the cost function as much as possible and consequently, θ0 = 250, θ1 = 0.12. Plotting those values on our graph to the right seems to put our point in the center of the inner most ‘circle’.

Doing this by eye/hand is time consuming, what is ideal is having an efficient algorithm for finding the minimum for θ0 and θ1.

Gradient Descent

- So we have our hypothesis function

- And we have a way of measuring how well it fits into the data.

- Now, we need to estimate the parameters in the hypothesis function.

- Gradient Descent Algorithm: To minimize cost function J

- Gradient Descent is used all over machine learning for minimization

- Gradient descent applies to more general functions

- J(θ0, θ1, θ2 …. θn)

- min J(θ0, θ1, θ2 …. θn)

- Gradient Descent Algorithm: To minimize cost function J

Problem:

- We have J(θ0, θ1)

- We want to get min J(θ0, θ1)

Imagine that we graph our hypothesis function based on its fields θ0 & θ1 (actually we are graphing the cost function as a function of the parameter estimates).

We are not graphing x and y itself, but the parameter range of our hypothesis function and the cost resulting from selecting a particular set of parameters.

We put θ0 on the x axis, θ1 on the y axis, with the cost function on the vertical z axis.

- The points on our graph will be the result of the cost function using our hypothesis with those specific theta parameters.

The graph below depicts such a setup.

(Note: Errata: The numbering of the vertical axis should be 0 through 6 (instead of -3 to 3), because cost is defined as a positive value.)

We have succeeded when our cost function is at the very bottom of the pits in our graph, i.e. when its value is the minimum.

The red arrows show the minimum points in the graph.

How does it work?

- Start with initial guesses

- Start at 0,0 (or any other value)

- Keeping changing θ0 and θ1 a little bit to try and reduce J(θ0,θ1)

- Each time you change the parameters, you select the gradient which reduces J(θ0,θ1) the most possible

- Repeat

- Do so until you converge to a local minimum

- Where you start can determine which minimum you end up at

(Note: Errata: The numbering of the vertical axis should be 0 through 6 (instead of -3 to 3), because cost is defined as a positive value.)

The image above shows us two different starting points that end up in two different places.

Depending on where one starts on the graph, one could end up at different points.

- Here we can see one initialization point led to one local minimum

- The other led to a different one

How do we make it work?

Taking the derivative (the tangential line to a function) of our cost function. The slope of the tangent is the derivative at that point and it will give us a direction to move towards.

We make steps down the cost function in the direction with the steepest descent.

- Size of each step is determined by parameter α a.k.a. learning rate.

For example, the distance between each ‘star’ in the graph above represents a step determined by our parameter α.

A smaller α would result in a smaller step and a larger α results in a larger step.

The direction in which the step is taken is determined by the partial derivative of J(θ0, θ1).

The gradient descent algorithm is:

Repeat until convergence:

θj := θj - α* (d/(d*θ1)*J(θ1,θ0)

(for j=1 and j=0)

where j=0,1 represents the feature index number.

Update θj on left side with respect to θj on the right side, based on above formula.

:= symbol means assignment.

At each iteration j, one should simultaneously update the parameters

θ0, θ1, θ2, …., θn.

Updating a specific parameter prior to calculating another one on the jth iteration would yield to a wrong implementation.

Suppose θ0 = 1, θ1 = 2, and we simultaneously update θ0 & θ1 using the rule θj := θj + (θ0*θ1)^0.5 , what are the resulting values of θ0 & θ1?

- θ0 will be 1 + sqrt 2 & θ1 will be 2 + sqrt 2

Gradient Descent Intuition

Understanding the algorithm:

In this chapter, we explore the scenario where we used one parameter θ1 and plotted its cost function to implement a gradient descent.

Gradient Descent algorithm:

Ignore θ0. So,

Repeat until convergence:

θ1 := θ1 - α* (d/(d*θ1)*J(θ1)

Two key terms in the algorithm:

- Alpha α

We should adjust α to ensure the gradient descent algorithm converges in a reasonable time.

Failure to converge or too much time to obtain the minimum value imply that our step size is wrong.

What happens if alpha is too small or too large?- Too small

- Take baby steps

- Takes too long

- Too large

- Can overshoot the minimum and fail to converge

- Too small

- Derivative term

- Take the tangent at the point and look at the slope of the line

- So moving towards the mimum (down) will greate a negative derivative, alpha is always positive, so will update j(θ1) to a smaller value

- Similarly, if we’re moving up a slope we make j(θ1) a bigger number

Notation nuances:

- Partial derivative vs. derivative

- Use partial derivative when we have multiple variables but only derive with respect to one

- Use derivative when we are deriving with respect to all the variables

Regardless of the slope’s sign for (d/(d*θ1)*J(θ1)) , θ1 eventually converges to its minimum value.

The following graph shows that when the slope is negative, the value of θ1 increases and when it is positive, the value of θ1 decreases.

How does gradient descent converge with a fixed step size α?

- (d/(d*θ1)*J(θ1)) approaches 0 as we approach the bottom of our convex function.

- At the minimum, the derivative will always be 0 and thus we get:

θ1 := θ1 - α * 0

Gradient Descent For Linear Regression

Recap: Previously, we talked about:

- Gradient descent algorithm:

- Linear regression model and the Squared error cost function

We want to apply gradient descent to minimise our cost function J(θ0,θ1), and that will give us an algorithm for linear regression for putting a straight line to our data.

Key term we need: the partial derivative term in gradient descent algorithm, (a/aθj)*J(θ0,θ1)

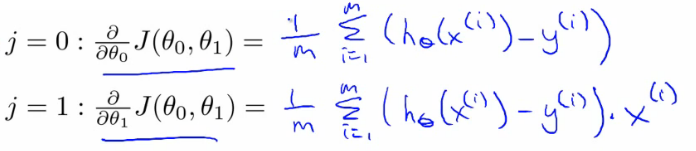

When specifically applied to the case of linear regression, a new form of the gradient descent equation can be derived. We can substitute our actual cost function and our actual hypothesis function into this partial derivative, and modify the equation to:

where m is the size of the training set, θ0 a constant that will be changing simultaneously with θ1 and xi, yi are values of the given training set (data).

So we need to determine the derivative for each parameter - i.e.

- When j = 0

- When j = 1

Figure out what this partial derivative is for the θ0 and θ1 case

- When we derive this expression in terms of j = 0 and j = 1 we get the following:

(Computing those partial derivative terms requires some multivariate calculus. If you know calculus, feel free to work through the derivations yourself and check. But if you’re less familiar with calculus, don’t worry about it and it’s fine to just take these equations that were worked out)

The point of all this is that if we start with a guess for our hypothesis and then repeatedly apply these gradient descent equations, our hypothesis will become more and more accurate.

This is gradient descent on the original cost function J. This method looks at every example in the entire training set on every step, and is called batch gradient descent.

While gradient descent can be susceptible to local minima in general, for cost function J(θ0,θ1) used in linear regression,

- it is always a convex quadratic function &

- there are no local optima (other than the global optimum);

- thus gradient descent always converges (assuming learning rate α is not too large) to the global minimum.

There exists a solution for numerically solving for the minimum of the cost function j without needing to use an iterative algorithm like gradient descent: the Normal equations method.

- Gradient descent scales better to large data sets though

- Gradient descent will scale better to larger data sets than that normal equation method

- Gradient descent algorithm will be used a lot in ML problems.